How NASA Builds Political Capital

Five Tactics for Generating Public Support for Ambitious Science

No government institution does a better job of marketing itself than NASA. Only the National Park Service and Postal Service are more popular—and they have the luxury of making tangible public goods easily attributable to them. In addition, NASA and space exploration have remained mostly above the frays of partisan politics even though overall trust in science is falling drastically.

While it’s easy to credit its popularity to something like the ‘exciting’ nature of space travel, I argue NASA’s public image and the very ways Americans conceive of space are deeply shaped by the agency’s intentional marketing efforts.

Some may be worried upon seeing a scientific domain’s public perceptions being intentionally influenced, by a federal agency no less. It’s more comforting to imagine science as a perfectly neutral process devoid of human subjectivity.

However, as someone who believes American culture & politics greatly underrate the importance of scientific and technological progress, I find comfort in knowing NASA successfully galvanizes American support for space. It proves that scientific ambition is not pre-determined by the random will of Washington policymakers, but can be actively swayed by intentional advocacy.

Therefore, those seeking to grow support for scientific endeavors, whether it be scientists, techno-optimists, or other federal science agencies, can learn from NASA’s tactics to win more popular support for their fields of interest, thereby gaining more political capital in DC for funding, new missions, etc.

A quick Internet search reveals that NASA dedicates significant resources to engage the American public in its mission. Just to name a few:

It operates its own on-demand streaming service with live launch coverage, kids' content, and Spanish-language programming.

It maintains the most wide-ranging ‘citizen science’ program by a federal science agency where anyone can contribute to a NASA project.

It offers extensive educational materials to teachers to facilitate K-12 space education.

It has featured or helped produce many well-known US cultural artifacts about space, such as the adventure movie “The Martian,” in which NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab plays a crucial role in safely guiding Matt Damon back to Earth.

These efforts are not nice-to-haves, but existential. Although space exploration has been part of the American cultural imagination as early as the 1800s1 and dominated public attention during the 1960s, most Americans did not support going to the moon except in the weeks leading up to Apollo 11. They consistently rank as one of the most popular agencies but are often a low spending priority for taxpayers.

Without its extensive PR efforts, its public and therefore political support would undoubtedly wane even further. Therefore, it operates an intentional, targeted, and adaptive strategy to build political capital—every last bit counts in generating Congressional appropriations.

This essay distills five tactics that NASA has consistently used to build public support: (1) Open and Decentralized, (2) Help Others Tell Your Story, (3) Heroes as Spokespeople, (4) Invest in Political Imagery, and most importantly, (5) Adapt to Public Sentiment.

These opinions are solely my own and do not represent any past or present employer. They were developed through various conversations and reading primary and secondary literature—primarily Congressional testimonies from 1960-2023, Politics and Space: Image Making by NASA, Marketing the Moon, and 50 Years of Solar System Exploration.

Tactic #1: Open and Decentralized

Some writers have described NASA’s PR efforts and its relationship with the media as a centralized bureaucracy, with every detail neatly choreographed. The opposite is true; key to NASA’s PR success is its open and decentralized approach to disseminating information and engaging reporters.

From its inception, NASA was juxtapositioned as a peaceful, civilian program against the Soviet’s secretive, military aims. The NASA Act of 1958 directed the agency to “provide for the widest practicable and appropriate dissemination of information concerning its activities and the results thereof.” The goal was, as a JPL Public Affairs Officer put it, to prove “one of the basic differences between our philosophy and the Russian doctrine. It is the difference between rubber stamp elections and free elections...it is the difference between a civilization that is sure and proud of its strength and a dictatorship whose insecurity must be protected by secrecy.”

Policies and organizational decisions were generally made with this philosophy. By design, the public affairs office was decentralized and, at least in the Apollo years, emphasized hiring former journalists. This set them up to operate “not as pitchmen but as reporters,” seeking to discover newsworthy information that various departments were working on and surface it to the press instead of pushing a top-down narrative.2

The exact degree of transparency differed based on leadership. The early years of the manned space program erred on the side of cautious openness, with careful branding of the Mercury astronauts with exclusive media contracts. By 1963, however, NASA adopted a policy of uncensored and instantaneous release of information, making it severely difficult to dictate a public image.3 Shortly thereafter, the pro-open faction secured a pivotal policy victory allowing journalists to access a wide availability of mission information before a launch, rather than after, as was the policy of the military.4

In addition, audio transcripts from astronauts were published uncensored and astronauts were encouraged to participate in more public speaking events.5 To this day, NASA continues to disseminate information openly, such as publishing detailed mission information in online databases.6

Tactic #2: Help Others Tell Your Story

NASA’s open and decentralized PR philosophy created a uniquely trusting and symbiotic relationship with the press. Brian Duff, former head of NASA Public Affairs, affirms that "the relationship between NASA and the media was a pioneering effort, in terms of cooperation and mutual trust, and, in more than twenty-five years, there were very few breaches of that trust on either side.”7

NASA’s relationship with the press gives it a powerful layer of abstraction against coming off as “sales-y.” By having others speak on their behalf, NASA can come off as an objective party merely providing public information as opposed to generating publicity. Walter T. Bonney, NASA’s first head of public relations, makes this distinction in a letter to Administrator Glennan: “The distinction between publicity and public information must be kept constantly in mind…[to] ‘sell’ facts or images of a product, activity, viewpoint, or personality to create a favorable public impression has no place” in NASA.8

This distinction results in NASA going to great lengths to make it as easy as possible for others to advocate on NASA’s behalf. Public affairs staff work as reporters within the agency, seeking out newsworthy information from NASA technical personnel and processing it into ready-made press kits.9 The press then re-uses press kits’ images and excerpts to make the news their own.10

During Apollo, NASA made press kits for print and TV reporters and offered technical Q&A briefings for journalists in advance of missions. They made materials that addressed reporters’ needs in sponsored media symposiums, “ready-made” clips for TV newsreels, and even distributed “fully produced interview programs of 14½ minutes duration” that radio stations could easily cut and air.11

NASA also helps contractors feature their role in space missions, thus giving NASA another vector to reach the public. During the early manned missions, NASA helped contractors create their own press kits and allowed them to feature NASA in their ads, including defense contractor Lockheed, Swedish camera manufacturer Hasselblad, and powdered drink mix Tang.12

Tactic #3: Heroes as Spokespeople

People naturally gravitate to heroes, so NASA has always leaned on astronauts to be public champions for the agency’s missions. A candidate’s potential marketability is also part of the initial selection criteria. Once selected, astronauts are required to take courses on public communication and learn how to “show your program in the best light.”13

Since astronauts are portrayed as “national champions,” they’re usually selected based on relatability and virtue.14 Making the astronauts seem relatable to the average American, while being an aspirational, larger-than-life figure, is the ideal balance.

NASA finds ample opportunity for astronauts to engage the public, including appearances at museums, state fairs, scientific and technical conferences, libraries, and universities. When I worked in Congress, I rarely saw a Congressional hearing room more packed than when the Artemis II crew held an open staff briefing. Many staffers were standing because we had run out of chairs, but everyone was eagerly listening to the crew describe their mission. They were all extremely eloquent and kept emphasizing the crucial role Congress played in making this possible (no doubt to stroke egos in the hopes of gaining more funding, as they should).

When the Apollo 11 crew returned to Earth after being the first humans to walk on the moon, NASA organized a 50-state celebratory tour and global Presidential Goodwill Tour that carried the astronauts and their wives to 24 countries over in 45 days.

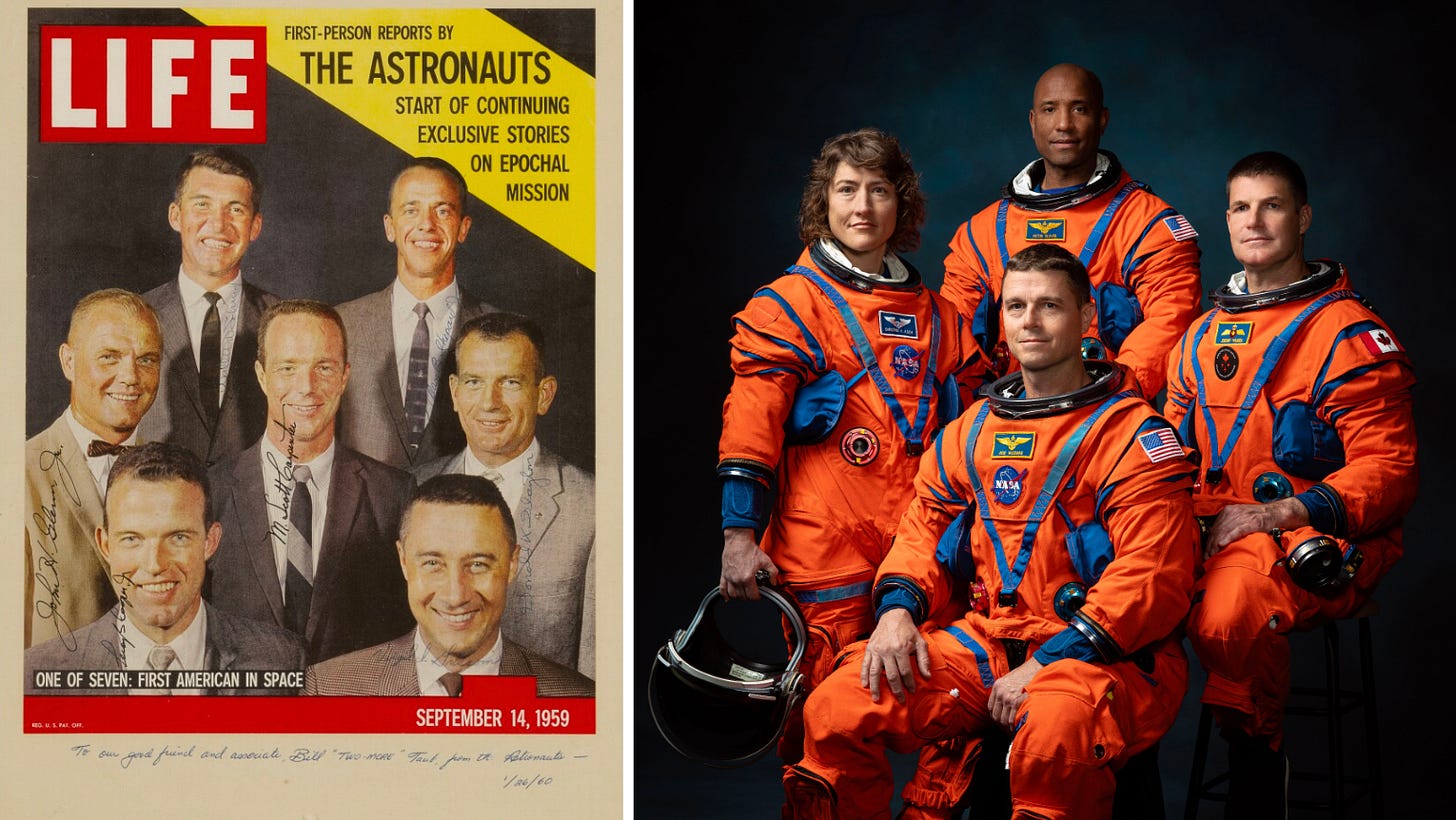

NASA also encourages astronauts to be prominently featured in media, none more infamously than the 1959 LIFE magazine deal. LIFE paid NASA $500K for exclusive access to the first group of Mercury astronauts.15 By spotlighting their relationships with “god, family, country,” the astronauts became overnight “national heroes.”16 However, guardrails must be implemented to avoid giving the impression that astronauts are individually profiting off taxpayer funding. Kennedy’s White House had to intervene when stories surfaced that astronauts had accepted offers of free homes from a real estate developer.17

Tactic #4: Invest in Political Imagery

While capturing images of supernovas and faraway galaxies is part of NASA’s scientific mission, they have the added benefit of generating excitement for its work. Therefore, NASA invests substantial resources into capturing media that will captivate the public imagination, sometimes even inventing new technology to do so.

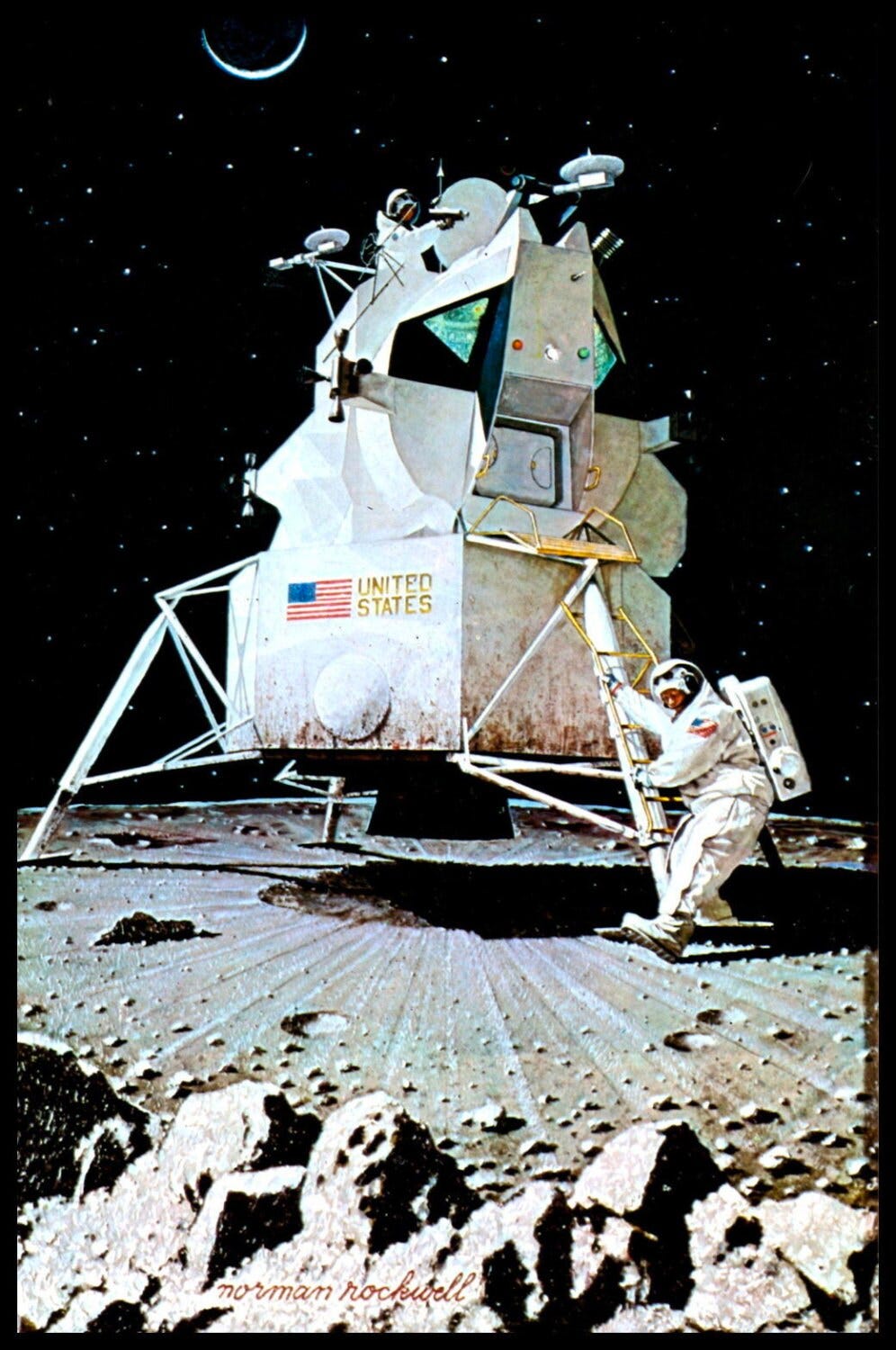

The live TV feed of Apollo 11 landing on the moon, watched by 650 million people, almost didn’t happen. For starters, the camera and networking technology at the time weren’t sufficient to support live streaming from an orbiting spacecraft. A strong anti-TV faction of managers and astronauts argued it was a waste of resources, that “performing” wasn’t in the job description, and that it would be a distraction. In response, the pro-TV faction commissioned Norman Rockwell, America’s most famous idealist painter, to paint man’s first step on the moon to generate public support for the idea.18 Eventually, NASA leadership approved the idea, and NASA subsequently awarded a $2.29M contract to Westinghouse to develop a TV camera that could operate in space.19

The Hubble Telescope is another example. While a useful scientific instrument to be sure, it has also served as one of NASA’s most effective PR investments—a multi-decade, $16+ billion telescope that has returned iconic images including the Pillars of Creation, Orion Nebula, and others, that have helped keep NASA in the public consciousness post-Apollo.

Tactic #5: Adapt to Public Sentiment

NASA’s most critical political-capital-building tactic is Adapting to Public Sentiment. Accomplishing significant feats in outer space requires immense resources, requiring NASA to adapt its goals, programs, and communications to the prevailing political climate to garner political and financial support.

Historian Mark E. Byrnes, in his 1994 book Politics and Space, argues that NASA’s three major projects until then—Mercury, Apollo, and the Shuttle—were devised and marketed under three distinct cultural epochs—nationalism, romanticism, and pragmatism—that captured the current political zeitgeist of why Americans supported space.20 Using Byrnes’s framework, we can identify roughly two eras post-1994: efficiency and international cooperation (1990s-2000s) and inclusion (2010s-present). NASA administrators’ Congressional budget testimonies show a clear transition from one epoch to the next.21 We selected testimonies from key moments in NASA's history: the first Mercury launch (fiscal year 1961), Apollo 11 (FY 1969), the first Space Shuttle flight (FY 1981), the first crewed mission to the International Space Station (FY 1998), the establishment of the Commercial Crew Program (FY 2011), and the anticipated Artemis launch (FY 2024).

The rest of this section will trace the historical arc of how NASA adapted its missions and public narratives to align with the prevailing political sentiment of the day.

NASA was founded in a cultural context that Byrnes deemed its nationalism era. Eisenhower was initially reluctant to create a civilian space agency because he wanted to prioritize military space applications, but following immense public pressure after the Soviet Union’s Sputnik I became the first satellite in Earth orbit, he acquiesced and formed NASA in 1958.22 Nonetheless, Eisenhower’s administration was primarily concerned with the potential security threats of Soviet space leadership, and thus NASA’s early communications focused on national security and catching up with the Soviet Union. To do this, they evoked national pride, international competition, and the security concerns of space in their external communications.23

In 1960, NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan went before Congress to present NASA’s upcoming budget and justify why US taxpayers should continue funding the 1.5-year-old agency.24 More so than any of the other testimonies we examined, Glennan’s testimony focused on the military applications of space research and the US’s strategic positioning vis-a-vis the Soviet Union. International collaboration was notably not a theme in his testimony, likely because the Soviet Union was the only other nation capable of considering a large-scale space program.25 Glennan’s opening statement began with a dire warning: “We are unable as of the present time, to match our competitor in the weightlifting capability of launch vehicle systems.”26 Glennan stressed that NASA’s key focus was to increase rocket capabilities to deliver increasingly heavier payloads, with Mercury being a crucial short-term test as the first manned orbital flight. Glennan concluded that once these capabilities were developed, “exploring the moon and nearby planets,” and “perfecting our communications, guidance, and propulsion systems” would become viable goals.27

As Glennan promised, NASA’s mission scope expanded in the following years as the agency’s technical capabilities advanced. However, the Soviets were also rapidly progressing, beating the US in sending the first living being (Laika the dog) and person to space by 1961. President John F. Kennedy decided to commission a manned moon mission before the decade’s end despite warnings from his science advisor Jerome Wiesner that unmanned activity should be prioritized, as manned missions were risky, gimmicky, and expensive.28 However, Kennedy wanted a lofty goal that the US—with its economic and industrial advantages—could achieve first and to distract from his administration’s early policy failures (most notably the Bay of Pigs). A Gallup poll taken right before Kennedy called for the lunar landing found that 58% of Americans opposed it.29

In the proceeding decade, NASA’s technical progress and the corresponding expansion deeper into space changed American perceptions about space from one centered on national security to scientific exploration and achievement. Byrnes characterized NASA’s aesthetics in the Apollo period to be one of romanticism, defined by themes of exploration, heroism, and curiosity. Neil Armstrong’s decision to celebrate his step as a “giant leap for mankind,” not “for America,” signifies the transition from seeing the US space program as a nationalist project to a humanist one. This shift was also present in the language of NASA leadership’s congressional testimonies. Whereas Glennan’s 1958 testimony highlighted US concerns about the Soviets’ lead and the security dimension of outer space, Administrator James Webb’s 1968 Congressional testimony on NASA’s upcoming budget paid much attention to neither. Instead, Webb’s testimony focused on the scientific achievements and discoveries from space exploration.30 He highlighted the successful completion of the unmanned lunar exploration program that provided the foundations for Apollo 11, the observation of plant growth in space for the first time, and various probes’ multi-hundred-million-mile journeys to study the sun and nearby planets, among others.

NASA’s happy times were not to last. Its external political environment began deteriorating in the mid-1960s due to the US's deepening involvement in Vietnam, economic instability, and political unrest. Space seemed too far away to matter. Even during the 1960s the majority of Americans did not believe space exploration was worth the $4B being spent annually besides a brief revival of public support just prior to and after Apollo 11.31 A 1970 Harris poll found that 56% of Americans did not believe going to the moon had been worth the cost.32 Coming from a breathtaking accomplishment that many thought was merely the beginning of space exploration’s golden age, the agency found itself attacked rather than rewarded.

NASA pivoted to what Byrnes described as its pragmatism era in the face of growing questions about where national priorities should lie. During this time, NASA shifted its emphasis to the practical benefits of space exploration. The agency stressed that the technologies invented for space missions, such as improved cameras, satellites, and more, had tangible economic benefits for all citizens. The Space Shuttle, billed as a reliable, reusable, cost-effective method of consistently providing access to Earth orbit, became NASA’s next signature project. When speaking publicly about the Shuttle, NASA officials would emphasize how the Shuttle would result in various technological spinoffs from fuel cells to new materials, reduce the cost and frequency of satellite launches, and principally, democratize space transportation—one day even making rides to space stations as simple as “flying on airplanes” or riding a “space truck.”33 NASA’s positioning of itself also clearly considered other macro-political forces in the 1970s, such as the early rise of globalization, stagflation, the development of other nations’ space programs, and the US’s expanding alliances amid the final decades of the Cold War.

These themes were evident in Administrator Robert Frosch’s 1980 testimony to Congress for NASA’s FY 1981 budget hearing, a year before the first Space Shuttle launch.34 His opening statement began immediately with an emphasis on US allies and the “international character of space activities” and promising that “the 1980s will be a decade when for the first time the life of almost everyone on Earth will be made significantly better by our ability to apply our skills in space to problems here on Earth.”35 He promised NASA would help the US maintain a leading role in meeting economic demands from the “free world market.” He goes on to emphasize major technological advancements that NASA has and will continue pushing, including satellites, weather prediction, and materials processing in space. The Space Shuttle was marketed as the agency’s prime contribution of “spur[ring] positive non-inflationary returns to our economy.”36

Although space exploration continued to find relevance in the 80s and 90s, such as through the proliferation of GPS and the famous images taken by the Hubble Telescope, taxpayer appetite to spend billions on large science projects waned with the fortunes of the Soviet Union. As one Nobel Laureate physicist reflected on the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC), another ‘big science’ initiative started during the height of the Cold War: “Spending for the SSC had become a target for a new class of Congressmen elected in 1992…they didn’t feel that much was at stake. The Cold War was over, and discoveries at the SSC were not going to produce anything of immediate practical importance.”37 As the US became the sole global hegemon, it sought to establish diplomatic ties with Russia and expand the international liberal order.38 NASA also had to contend with a growing backlash against government overreach and wasteful spending from prior decades, famously resulting in the ‘Gingrich Revolution,’ in which Republicans won a landslide victory in 1994, gaining a majority in the House of Representatives for the first time in 40 years.

In response to this environment, NASA’s core theme became efficiency and international collaboration in the 1990s and early 2000s. It made program cuts and process overhauls to curb program cost growth and increase the percentage of funding spent on R&D instead of administrative tasks. Administrator Daniel Godin testified in 1998: “In 5 years, we have turned an average program cost growth of 77 percent to underruns of 6 percent…we have cut the number of civil service employees by 5,000 since 1993.”39 Godin also emphasized the value of international partners, who contribute both financial resources (thereby reducing US taxpayer burdens) and technical expertise. He even credited the Russians, unthinkable just a decade prior: “Let me tell you, we would not be as far along today if the Russians hadn't entered the picture 3 years ago. We want the Russians as our partner.”40

Unfortunately for Godin, he led the agency during the lowest amount of public support for NASA funding and ambitious science in recent history,41 so he positioned NASA as the antidote against America’s waning ambitions: 42

“America was built on the blood and dreams of people who dared. Our founding fathers risked hanging and treason to give us freedom. Lewis and Clark risked the unknown to chart this country. We fought fascism. We created computers and the Internet. We sent men to the moon and brought them back safely. Bold dreams are full of the potential for failure. But today I'm concerned. Today I see some people and organizations in America not shooting for the stars, but shooting for a passing grade. NASA shows our children risk-taking is acceptable…We are about the hopes and dreams of America.”Godin’s testimony reflected a sentiment among America’s space champions that the nation had lost its way. Many reminiscenced the golden age of Apollo, leading President George Bush to create the Constellation program in 2005. Its two major goals were to complete the International Space Station and return to the Moon no later than 2020. However, due to budgetary constraints, the Obama administration discontinued the Constellation program in favor of the Commercial Crew program, which would replace NASA-internally-developed vehicles for cheaper industry solutions. This caused a bipartisan uproar in Congress, with Members decrying commercial solutions were “unproven” at best and “threatened our leadership in space” at worst.43 Democrat Representative Alan Grayson decried the plan’s “basic lack of vision.”44 Administrator Charles Bodin defended the administration’s decision in a 2011 testimony to Congress, arguing it was a “more sustainable and affordable approach to human space exploration.”45

Responding to both nostalgia for America’s golden age, as well as America’s cultural shifts in the 2010s, NASA reinstated its plans to return to the moon with a new theme unseen in previous eras: inclusion. The agency announced in 2017 that it would establish the Artemis I program to carry humans beyond low-Earth orbit for the first time in more than 50 years by 2024 and return astronauts to the Moon’s surface by 2025, with a keen emphasis on landing the first woman and first person of color on the Moon. This contrasts with when NASA first launched the moon program, it intentionally selected and trained “typical" Americans—clean-cut, white, adventurous, and Protestant.46 Administrator Bill Nelson emphasized NASA’s new approach in his 2023 budget testimony, emphasizing that Artemis was the result of the “broadest exploration coalition in history, including multiple international and commercial partners…and will enable the first woman and person of color to walk on the Moon.”47

A Voyage to the Moon (George Tucker, 1823); The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall (Edgar Allan Poe, 1835); From the Earth to the Moon (Jules Verne, 1865);

Marketing The Moon, 17-21.

Ibid, 31-32.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Marketing The Moon, 18.

Marketing The Moon, 18.

Ibid, 21.

Ibid, 35-48.

Ibid, 38; 50 Years of Solar System Exploration: Historical Perspectives, 340.

Marketing The Moon, 19-22.

The Right Stuff, 34-40.

Marketing The Moon, 19.

Ibid, 55-62.

Ibid.

Budget testimonies are the best indicators of what NASA perceives to be Congress’s priorities—and therefore the public’s.

The Heavens and the Earth, 142-145.

History of Europe in Space. European Space Agency.

Ibid, 23.

The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1935-1971 New York: Random House, 1972), 1720.

"Public Favors Moon Landing" (Louis Harris, 14 July 1969); Politics and Space: Image Making by NASA, 95; The Moon Landing was Unpopular Before it Happened (Pessimists Archive Newsletter)

Harris Survey Yearbook of Public Opinion, 1970 (New York: Louis Harris & Associates, 1971), 83-84.

Politics and Space: Image Making by NASA, 116-120.

Ibid, 858.

Ibid.

The Crisis of Big Science (The New York Review of Books).

Ibid.

Ibid.