Everyone has a theory of history, consciously or not. A theory of history is your explanation for why things happen the way they do. It not only determines how one interprets events but also how one chooses to affect change in the world.

While theories of history are usually judged on their descriptive accuracy, another way to evaluate them is on their narrative power. How psychologically compelling are they for motivating behavior?

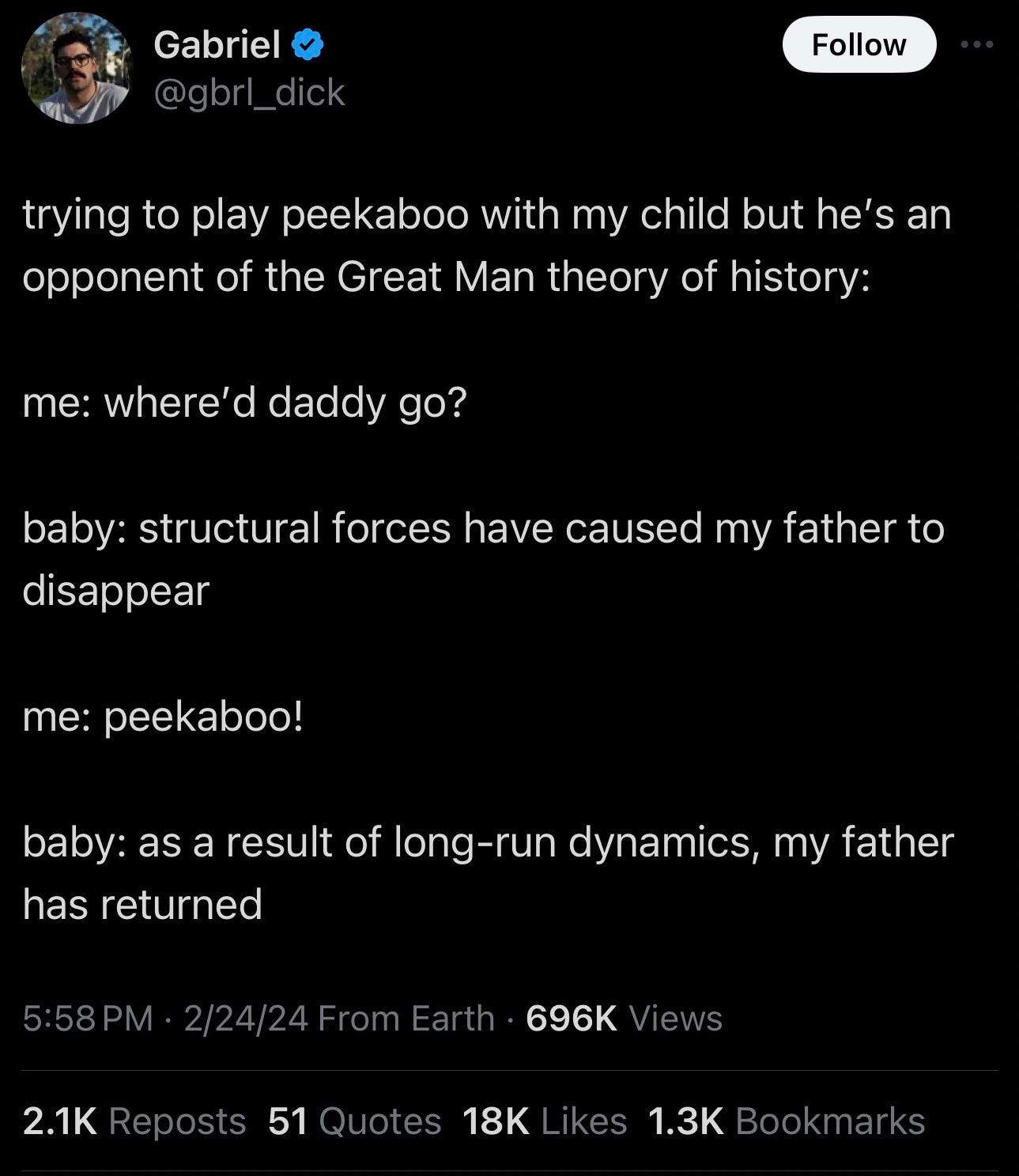

Historical models that emphasize individual will—what I call agentic theories of history—are the most personally motivating. Great Man Theory is the canonical example; those inclined to believe history is driven by great leaders often see themselves as one, pushing them toward greater ambitions than most.1 Similarly, religious narratives can also be highly agentic, where belief in a divine calling to participate in the struggle between good and evil can spur great sweat and sacrifice, a la the Protestant work ethic and martyrdom.

Of course, agentic theories of history can be taken too far. One can end up like Raskolnikov, who used Great Man Theory (“Napoleonism”) to justify his delusions of grandeur. Or consider the religious ferocity of King Philip II of Spain, who in seeing himself as God’s righteous representative on Earth ("I undertake to deal with everything necessary to achieve all this—I shall never fail to stand up for the cause of God"), bankrupted his empire 4x with miscalculated holy wars.

One must balance agency and humility, but this is difficult in practice. All things being equal, it is preferable to over-index on the former. If you believe you have agency over a situation you might, but if you don’t then you guarantee none.

If some theories of history are agentic, then others must be anti-agentic. Such theories minimize the role of human will in driving history, instead preferring factors outside individual control.

These anti-agentic models of history can take many forms. Predestination is the simplest kind—while humans remain featured as history’s driving force, their motivations and abilities are explained by supernatural powers. Most associate predestination with homo religiosus, such as the Calvinists, who hold that God chooses who is saved or damned irrespective of anything we do. However, plenty of secular flavors exist as well, such as (perhaps surprisingly), Carlyle’s original formulation of Great Man Theory—he claimed great men are born with divine attributes, not made.

The more egregious type of anti-agentivity removes the human entirely, replacing it with a singular, external, mechanistic explanation for history. Examples include genetic determinism, geographic determinism, historical materialism, and technological determinism, which respectively explain social developments as primarily an outgrowth of genes, geography, technology, or its use in economic affairs (i.e. the “modes of production”). These are all varying sides of the same coin; such explanations reduce humans to passive brains on sticks, subservient to forces outside the will, intellect, and flesh.

Let me be clear—a theory of history’s agentivity has no bearing on its accuracy. It is obvious that our lives, countries, and civilizations are shaped by many forces outside of the human. My critique of anti-agentic theories is not on their truth value, but rather that over-believing their predictive power can cause us to reduce reality to “If X, then Y” inevitabilities. At the individual level, this sense of inevitability induces fatalism—why try at all if the future is pre-determined?

I worry about a particular flavor of anti-agentic history that has surged in popularity in recent years: cyclical theories of history. They explain history as a series of inevitable rise-and-fall cycles, driven by Fortuna greater than any individual Virtù.

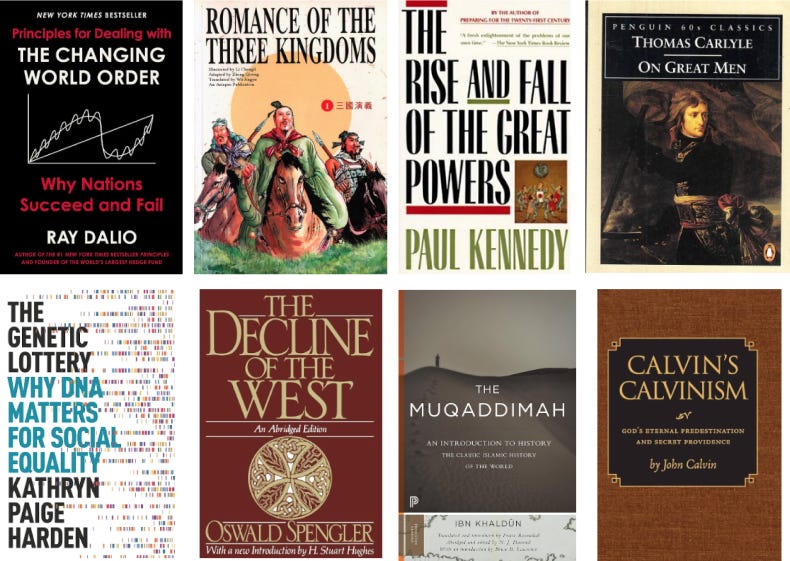

Such theories are not new. Polybius, a Hellenistic Greek historian, was the first in the West to articulate a cyclical structure to political history under his theory of anacyclosis. Predating him were Hinduism’s Yuga cycles and China’s Mandate of Heaven doctrine, enshrined in the first line from Romance of the Three Kingdoms: “The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has always been.” Ibn Khaldun, the famed 14th-century Arab historian, credited ‘asabiyyah’ as the driving force of historical cycles. Modern versions include Strauss–Howe generational theory, Spengler’s Decline of the West, and Kennedy’s Rise and Fall of Great Powers.

What is new, however, is the extent to which we use cyclicality to comfort ourselves about the future. For instance, today it is common to console oneself that we need not worry about polarization because partisanship has always waxed and waned. Therefore, one day normalcy will inevitably return. Similarly, in our anxieties about the risks of AI, we comfort ourselves with the cyclical narrative that technological automation, though always initially resisted, inevitably proves vastly beneficial. The AI Luddites must be fully dismissed.

The historian’s task is greatly simplified with a cyclical framing of history. By shrouding historical nuances in systemic patterns, we get to ignore the individual actions and idiosyncratic conditions that history is contingent on. Pretending history follows a singular Hegelian rationality makes it reducible to oversimplified generalities.

Today’s US-China tensions were partly birthed from such naive reductionism. With the Soviet Union’s decline, the US thought communist authoritarian regimes would inevitably fall against the strength of Western capitalism. Some even declared liberal hegemony marked the end of history itself. The US led the charge to integrate China into the globalized economy, assuming economic liberalization would accelerate the inevitable next phase of political democratization.2 However, Chinese leaders rejected this cyclical view. The fall of the Berlin Wall taught them a very different lesson: perestroika without glasnost would be the key to survival.

Induced intellectual laziness is only the second harm of a cyclical interpretation of history. The stripping of agency is the far more nefarious effect. If history really is a succession of inevitable patterns, then humans are subordinated to playing passive spectators.

Unfortunately, this loss of agency is precisely what makes cyclicality so appealing. If the future is pre-determined, we are freed from having to think about it too hard. We can just surrender to the flow. Loss of agency festers existential cynicism—it is no wonder that it has become trendy to be depressed, or at least to signal that you are.

Again, do not mistake these critiques as an all-out dismissal of cyclicality—or anti-agentic theories of history more broadly. These models have plenty of valuable insight to offer. Cyclical analyses of states and civilizations (e.g. Khaldun, Spengler, Kennedy, Dalio) highlight the key drivers of state growth and decline: financial and economic power, military strength, cultural unity, etc. These multivariate analyses can inform statesmen about what issues to prioritize.

My concern is not with the theories themselves, but how we use them at the individual level. Obviously, there are no immortal societies; every society has risen and fallen. The problem arises when applying such theories to one's own life and society.

Reading Spengler, Kennedy, or Dalio, one might conclude the US/West is locked in an inevitable decline. Indeed, accusations that the US is a declining power have become so frequent it borders on the cliché. This may well be true, but the accusation is less important than the motivation of the accusers—more often than not, I find that this thinking is used to justify not participating in civic life or matters of national importance (“We’re screwed anyway, so I might as well focus solely on myself”).

Herein lies the final danger of cyclical theories of history: it seduces us to become bystanders of history rather than agents of it. The more you believe in the wheel’s inevitability to turn, the more you hasten its acceleration. Instead of asserting your agency, you let history wobble towards the outcome you predestined.

This mode of being can be harmful to individuals, and at scale, destructive to society. Ancient China offers many cautionary tales of the former—and its entire history is a warning of the latter. In the waning years of the Western Han Dynasty, many court officials interpreted the country’s economic troubles to mean the dynasty was at the end of its Mandate of Heaven cycle. They switched sides to Wang Mang’s briefly-usurpacious Xin Dynasty, only to be later executed when Han Guangwu restored the Han Dynasty. At the macro level, belief in the inevitability of dynastic cyclicality trapped Chinese politics in the dynastic paradigm for thousands of years, only collapsing under the external pressures of Western and Japanese imperialism.

Cyclicality limits the imagination, substituting what can bewithwhat is. This isn’t so bad for the historian, who in embracing cyclicality, will be descriptively more-or-less accurate in describing the rise and fall of past nations. But for anyone seeking to make history, such an anti-agentic orientation towards the past can cripple how they create the future. Inevitability is the coward’s way out; reject the urge to retreat underground.

Thank you to Rachel Yee, Liz Dorman, Adi Sharma, and Andrew Song for their feedback on this piece.

Works like Will Durant’s Story of Philosophy and Robert Heilbroner’s Worldly Philosophers share this Carlylian orientation to trace the evolution of philosophy and modern economics through great individuals.

“In the knowledge economy, economic innovation and political empowerment, whether anyone likes it or not, will inevitably go hand in hand.” – Bill Clinton, 2000

Loved the historical context throughout! Anti-agentic worldviews seem to be an (unfortunately) timeless coping mechanism for the difficulty of making the future and disrupting flows of history :)